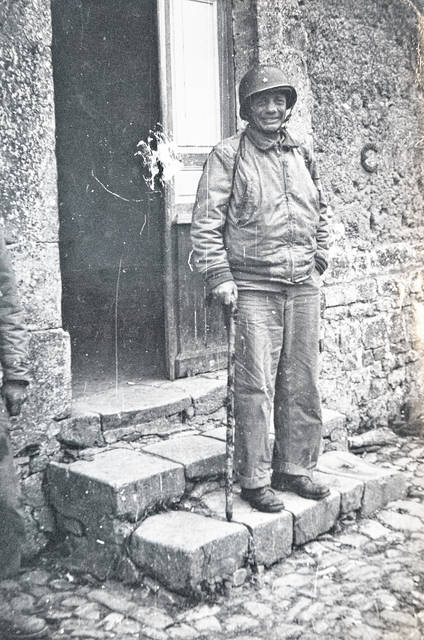

The cane once used by Brig. Gen. Teddy Roosevelt Jr., 4th Infantry Division, to direct his troops as they hit Utah Beach on D-Day will be donated to the Musée du Débarquement (D-Day Museum) in France next week. The general was the oldest son of former President Teddy Roosevelt.

Beth Rieman, a Delaware resident who has a curiosity for genealogy, was exploring some carefully preserved letters, military orders, and hometown newspaper clippings that followed the military career of her great-granduncle, James S. Rodwell, when she was led to an unbelievable discovery — her uncle’s close friendship with his commanding officer and the cane he used during the invasion.

“(Roosevelt) got the cane during World War I when he was shot near his knee,” Rieman said. “That’s why he needed a cane.”

Next week, Rieman is scheduled to fly to France to share her rare fine with the world when she donates the cane to the museum, where it will be placed in a display case with other D-Day relics.

“This specific museum is built on the sands where D-Day happened,” she said. “It sits where the cane was, and Teddy Roosevelt Jr. is buried there.”

Rieman said her family talked about hanging onto the cane along with all the documents, photos, and newspaper clippings, but “it was clear he was proud of his service and we felt like he wanted his legacy to be known.”

“This whole time it felt like one thing after another was falling into place for us to discover (the cane),” she added. “We felt that if we keep it in the family, we didn’t know if three generations down the road it would be sold. So giving it to a museum kind of felt like more people would see his story along with Roosevelt’s.”

Looking closer to home, the family contacted America’s National WWII Museum in New Orleans.

“They acted differently about it,” Rieman said. “The museum in France acted almost as excited as we were — almost tearful. They sent us pictures of the case where they will put it. They have a display of Teddy Roosevelt Jr. and all those types of things.”

Rieman said the National WWII Museum people seemed to have the attitude of us giving them the cane as if it were “hand-me-downs.”

“‘Sure, we’ll take it off your hands. We have a wax figure of Roosevelt in the corner we can put it with him,’” the museum told Rieman.

Rieman added the main difference between the two museums is in Normandy there is a large area dedicated to the brigadier general and his troops.

“There is something about this finally coming to rest where it all happened,” she said. “The people who go to the museum go to honor somebody that was there or to just be there where it happened.

“It feels right,” she added.

In fact, the Musée du Débarquement paid for Rieman’s plane ticket to take the cane to France.

“I was surprised that the museum paid, because we didn’t want to ship it,” she said. “In my mind, it’s going to get lost or broken. I’m not even going to put it in the luggage compartment. I’m going to carry it. I don’t want it tossed in the belly of the plane or lost like luggage does sometimes.”

Rieman will stay in a bed and breakfast while in France.

“I’m excited about the place I’m staying,” she said. “It’s neat looking.”

Rieman added the rooms of the bed and breakfast are named after Barton, Roosevelt, and others from D-Day.

“It’s kind of cool,” she said.

Rieman said she wants to take a day while there to walk in the footsteps of those who landed there on D-Day and let the cane touch the sand one last time. She said it feels like the cane is coming full circle by returning to Normandy.

“It’s going to be bittersweet, because it feels like it’s coming full circle,” she said. “It’s honoring the friendship of my uncle and Roosevelt.”